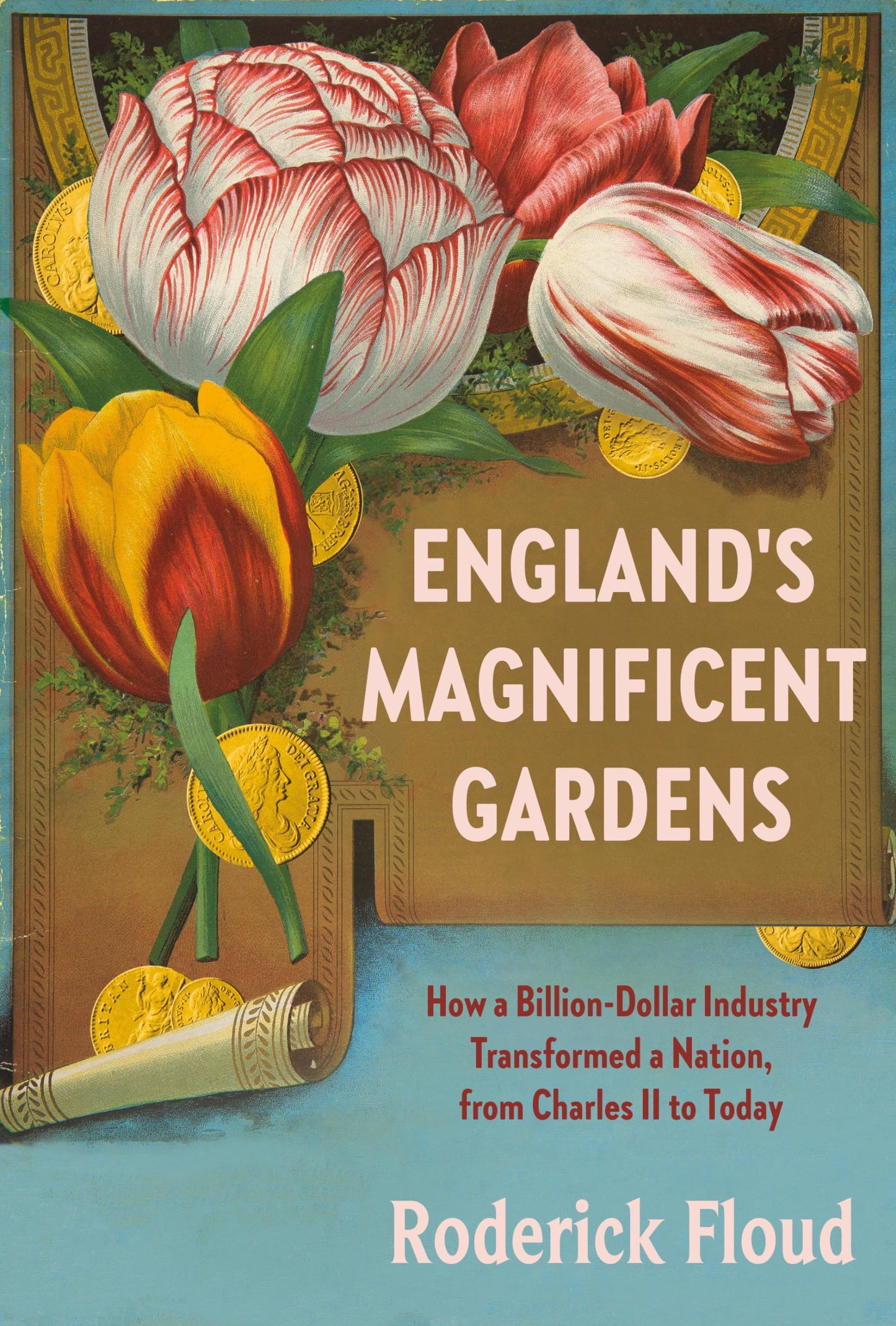

(TXS) England's Magnificent Gardens (very faint remainder mark) by Roderick Floud

(TXS) England's Magnificent Gardens (very faint remainder mark) by Roderick Floud

125 in stock

Couldn't load pickup availability

Author(s): Roderick Floud

Pub: Pantheon Books

Pack Qty: 13 (Paperback)

ISBN: 9781101871034 - New

Subjects: History, Europe, Great Britain, Crafts, Hobbies & Home, Gardening & Landscape Design, Garden Design, By Region

236mm x 173mm x 32mm

Publication: 15 June 2021Pages: 432

An altogether different kind of book on English gardens'the first of its kind'a look at the history of England's magnificent gardens as a history of Britain itself, from the seventeenth-century gardens of Charles II to those of Prince Charles today.

In this rich, revelatory history, Sir Roderick Floud, one of Britain's preeminent economic historians, writes that gardens have been created in Britain since Roman times but that their true growth began in the seventeenth century; by the eighteenth century, nurseries in London took up 100 acres, with ten million plants (!) that were worth more than all of the nurseries in France combined.

Floud's book takes us through more than three centuries of English history as he writes of the kings, queens, and princes whose garden obsessions changed the landscape of England itself, from Stuart, Georgian, and Victorian England to today's Windsors.

Here are William and Mary, who brought Dutch gardens and bulbs to Britain; William, who twice had his entire garden lowered in order to see the river from his apartments; and his successor, Queen Anne, who, like many others since, vowed to spend little on her gardens and instead spent millions. Floud also writes of Frederick, Prince of Wales, the founder of Kew Gardens, who spent more than $40,000 on a single twenty-five-foot tulip tree for Carlton House; Queen Victoria, who built the largest, most advanced and most efficient kitchen garden in Britain; and Prince Charles, who created and designed the gardens of Highgrove, inspired by his boyhood memories of his grandmother's gardens.

We see Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, who created a magnificent garden at Blenheim Palace, only to tear it apart and build a greater one; Deborah, Duchess of Devonshire, the savior of Chatsworth's 100-acre garden in the midst of its 35,000 acres; and the gardens of lesser mortals, among them Gertrude Jekyll and Vita Sackville-West, both notable garden designers and writers.

We see the designers of royal estates'among them, Henry Wise, William Kent, Humphrey Repton, and the greatest of all English gardeners, 'Capability' Brown, who created the 150-acre lake of Blenheim Palace, earned millions annually, and designed more than 170 parks, many still in existence today. We learn how gardening became a major catalyst for innovation (central heating came from experiments to heat greenhouses with hot-water pipes); how the new iron industry of industrializing Britain supplied a myriad of tools (mowers, pumps, and the boilers that heated the greenhouses); and, finally, Floud explores how gardening became an enormous industry as well as an art form in Britain, and by the nineteenth century was unrivaled anywhere in the world.